During the 1950s and into the 1960s St Kilda became more and more impoverished and its infrastructure increasingly 'run-down'. In the 1960s demand for inner city accommodation began to return which begun a short lived boom in apartment building boom.1

This apartment boom was a portent of future increased demand for inner city living. Increasing local traffic and traffic passing through the Junction 'too or from' more distant locations of Melbourne's expanding suburbans and beyond was overwhelming its infrastructure and capacity. The Junction must have had an atmosphere of 'dwindling order against rising chaos'. The solution decided and eventually implement was a significant physical and engineering redevelopment of the Junction.

Partial completion of the Junction's redevelopment

The Junction Hotel in the background just before its demolition

This was a technical solution typical of its era and attempt to provide a technocratic solution to a problem that involved more than just traffic flow difficulties. Other aspects associated with the Junction (e.g. local amenity) were not on the radar of the designers and their political masters, the focus was 'traffic control and management'.

The 1970s redevelopment with it's fly-overs, underpasses, street widening and demolitions imposed a harsh formality of form and functionality over the Junction. It physically remodelled the Junction to serve the convenience of the commuter and satisfy their need to get to their destination more easily and quickly. However, the redevelopment also created a long lasting and significant barrier cutting St Kilda in half in a much harsher physical form than the pre-existing Junction. Since it was built the physical form and visual harshness of the Junction has barely changed. Its austerity has perhaps softened a little by vegetation planted as simple landscaping, thickening and maturing. The traffic use of the Junction has continued to increase and in contrast St Kilda itself has undergone some dramatic changes since the completion of the 1970s redevelopment.

Construction of Queen's Way

The competed Queens Way

The increase use of the Junction has been in part driven by Melbourne's general population growth, the total number of vehicles (including trams and buses) and the number of journeys through the Junction made by those vehicles. Concurrently the economic fortune of St Kilda began to accrue bringing substantial social and physical change. This rising economic fortune was associated with an increasing demand for inner city living in suburbs like St Kilda. This demand has been driven by wide range of forces which were not only occurring in Melbourne but were part of an international phenomena that has been experienced across the world. These forces included a complex mixture of demographic, economic, social and cultural factors. The need to accommodate the rising demand for properties in St Kilda fuelled an impetus to redevelop old properties either by renovation and recycling or demolition and new building.

The redevelopment impetus of this era was a return to an old favourite Melbourne activity, 'property speculation' via 'land subdivision' and was geared to catering to the communities perceived notions of property ownership with the principle motivation of financial gain. Financial gain for the developer and building industry (via sales from the development), government agencies (via fees and charges - stamp duty) and financial gain by the home owner (via the expected growth in rents or the capital worth of their property).

Some of the consequences of this redevelopment was the demolition of many of the older mansions and other earlier buildings and their replacement with higher and more densely packed apartment buildings and town houses. The changes to building stock and its use fuelled conflict between local residents/institutions and the developers and their supporters. The impact of this redevelopment also contributed increases in property value and the cost of accommodation (e.g. rents). This conflict between local and developer/supporter interests also contributed to the establishment of opposing protest and actions groups and fostered the influence of the heritage and urban conservation movement.

By the mid 1980s the impact of redevelopment in St Kilda lead to the establishment of the 'Turn the Tide' political group.2 The 'Turn the Tide' group was successful in some of its objectives, such as the termination of the tourist development proposal for the St Kilda Marina, new height controls for buildings on the foreshore, new heritage control measures and the allocation of Council rates to support local social housing projects.3 In more recent times another community action group, 'unChain St Kilda' had its success by gaining Council representation (as did 'Turn the Tide'_ and in 2009 halted the proposed St Kilda Triangle project around the Palais Theatre. Since 2009 and under influence of 'unChain St Kilda' the Port Phillip Council has developed an alternative project concept. Another local action group was/is 'JAAG: Junction Area Action Group'. This group was more closely associated with the physical location of St Kilda Junction and has existed in at least one guise since 2002. It claims to represent the residence the Junction precinct bounded by St Kilda Road, Alma Road Chapel Street and Dandenong Road. Part of JAAG's mission statement is to 'strive to preserve our highly sought after sense of community values and protect our much loved local heritage buildings and streets capes ...'.4 The local identity of the Junction Precinct is heavy influence by the physical boundaries created by the 1970s redevelopment. The widening of the old High Street to extent St Kilda Road to Carisle Street and the creation of the Queens Way extension to link Dandenong Road with the Junction.

The aggregate success of the opposition movements to the inner city redevelopment impetus is questionable given the continued and increasing pressure to exploit and redevelop these areas. There has been some high profile and other successes but these movements have hardly dinted the increasing momentum for redevelopment. However, they have mitigated some of the worst excesses of the redevelopers but they have also stifled projects that were seen as benefical by other members of the community. Determining if a good or bad outcome has been achieved depends on the which side of the conflict and which values are seen more preeminent. To justify their position and actions each side draws upon their own selected ideological framework and supporting arguments and is motivated by their own interests (be that personal or communal). Each participant has at the germ of their position a desire to see their values and interests triumphant. Less scrupulous on both sides disguise their narrow vested interests as either serving the benefit and welfare of the wider community or by promoting their vest interests as the interests of the wider community itself.

The following links are to several short video clips from YouTube that relate to the 'St Kilda Triangle Project'. They illustrate how a development project can be judged and the values an individual may draw upon to justify their opinion and judgement. Focusing on the impact of the 1990s real estate boom, the last two video clips also provide commentaries and reminisces by local inhabitants about the social changes in St Kilda over four decades.

- St Kilda triangle site (this link will take you to YouTube)

- Spencer McLaren: St Kilda has to stay Culturally rich! (this link will take you to YouTube)

- Junkyard of Dreams Part 1 (this link will take you to YouTube)

- Junkyard of Dreams Part 2 (this link will take you to YouTube)

The 1980s ended with a global recession and an Australian recession that put a pause on the increase redevelopment occurring in suburbs like St Kilda only to later help accelerate this redevelopment by making residential development in the inner city more economically viable. Other changes in the 1980s and early 90s also contributed the 1990s redevelopment acceleration, which included the departure of manufacturing and warehouse businesses from the inner city leaving vacant exploitable properties, the reduction of the size of households reducing the space needed for occupancy and legislative changes encouraging denser housing and dual occupancy, etc.5

After the 1990s recession Australia enter a period of long prosperity and the demand for inner city living continued to increase. The people making this shift back to inner city living and contributing to the demand for inner city properties are often referred to as gentrifiers. The impact of the gentrifiers has been demand for higher amenity, increased property prices creating higher rents and pushing out the existing lower income residents and radically altering the social demographics of an area.6 St Kilda's social, economic and demographic makeup has been profoundly altered, including the loss of much of its indigenous community which had a strong presence in the 1980s.7

Gentrifiers were not just purchasers of newly built properties they also were a significant force in the acquisition of older properties, many with the objective of restoring them to some subjective notion of 'pass glory' and then either residing in their creation or selling it and moving on to the next venture. As well as a subjective restorative motivation most gentrifiers were/are also motivated by profit (e.g by increased rental income and/or the capital gained by the renovators property's increase in value). Gentrifiers having the capital to invest tended to target areas where property prices are relatively lower but had the potential for growth in short to medium term, had a suitable location and housing stock (all be it round down) and the potential for increased future demand as well as some heritage/cultural significance that could be exploited. The 'renovating gentrifier' was a hybrid mix of the developer and the urban/heritage conservationists. Gentrifiers (myself included being at one stage one of those St Kilda 'renovating gentrifiers') mixed elements of both the developer and the conservationist to suit their own motivations and objectives. Sometimes successfully and sometimes disastrously, either way their collective action contributed to the upward pressure on property prices and facilitated social and demographic change.

Gentrification began in the 1980s in St Kilda and accelerated in the 90s contributing to the area's many demographic, social and economic changes during this period.8 The Junction however, felt little of the dramatic changes going on around it except for the steady increase in traffic and use over that same period. There was some redevelopment in the Junction's immediate environment but this did not make any significant impact on the Junction itself except for the occasional rumblings about its ugliness, poor of space and lack of amenity for residents.

After a long period of stasis, in the past decade things have begun to change for the Junction. The immediate area surrounding the Junction has finally started to feel the same pressure and attention as the rest of St Kilda and has been target by developers for exploitation. This attention has become more intense with the increase in frequency and size of the projects being proposed. Currently there is a 18 storey 'the Icon' currently under construction at 2-8 St Kilda Road on the corner of Wellington Street and a 23 storey building with approval for 3-5 St Kilda Road with others in the pipeline.

The development push has resulted community resistance concerned about the impact of these development on local amenity and facilities. This is not unreasonable given that many of these project seek dispensations from Council planning controls. Concern is also justified given that there does not seem to be an area plan to integrate these individual projects, plan for the necessary amenities required by the future residents and make some meaningful of attempt to facilitate community integration. The City of Port Phillip has come under criticism for its slow reaction to the change occur at the Junction. Some have suggested that the failure of the Council to have binding height overlays has contributed success of these projects through the appeal process at the Victorian Administrative Appeals Tribunal and their approval by the Tribunal.9

'The Icon' a 18 story building at 2 St Kilda Road from 2015

Construction started in 2013,

the building was clearly designed to make its own powerful visual statement over the area

In 2006 the City of Port Phillip instituted a street art project at the Junction not without some local criticism.10 The motivation for the project may have derived from a range of factors such as; the cost of maintenance and cleaning, a desire to engage in a more constructive way with street artists, a desire to facilitate community involvement and commitment by participating is this sort of project, an attempt to attract tourists or an attempt to mitigate the perceived ugliness of the Junction. The project has become well known in the 'street art' community both nationally and internationally and is referred to in some quarters as the 'subterranean street art precinct'. The Street Art Project was significant for the Junction in two important ways. To my knowledge it was the first community interaction with the Junction for many years that did not involve some utilitarian function (e.g. maintenance) or traffic management issue. This project was the first time for many years that the Junction was associated with something other than traffic and positive attempt to improve the poor status of the Junction with the community.

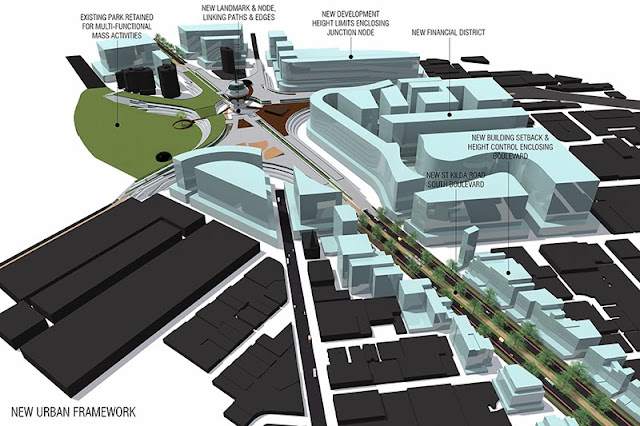

Another indication that the Junction is in need of an urban make-over is via some new design concepts produced by the University of Melbourne's Environments and Design Student Centre. The aim of the designs to improve the amenity, and functionality of the Junction by reconnecting the local community and to make the Junction a major multi-nodal transport interchange and a thriving residential and cultural precinct. Unfortunately to date no such integrated urban planning approach has been employed to take the Junction into the twenty-first century.11

One example of a design concept for St Kilda Junction from the University of Melbourne 2013

A recent criticism was made by Steve Dunn president of the Victorian Division of the Planning Institute of Australia who was commenting on the Junction as one of Melbourne’s worst planning disasters, a place that hampered traffic flow, isolated communities or disregarded amenity. He went onto say it was a complicated intersection that turned into a ‘traffic sewer’ at peak hour.12 Leo van Schaik, Professor of Architecture at RMIT has described St Kilda Junction as the most disappointing urban space in the city. He goes on to suggest it used to be an interesting hub but traffic engineers improved it into oblivion.13

Perkin’s harsh criticism has to be seen in the light of the design features of the Junction being out of date with twenty-first century expectations. Grumblings about the ugliness and lack of amenity have been going on for decades but as the 'street art' and 'design concepts' indicate there is some movement towards addressing these concerns.

Tram interchange at St Kilda Junction 2012

The current targeting of the Junction area by developments is going to change the Junction bringing more people to the immediate area. The pressure for better utilisation of the Junction for purposes other than being just a road intersection and tram interchange must surely increase with every development project completed.

The history of St Kilda Junction started at a time when devastating change was brought on the Boon wurrung people by European settlement. The Junction was a central focal point for the early St Kilda and helped feed the development and multiple changes to the area over time. It also maintained an important link with the Central Business District and the expanding suburbs of the south and southeast. Its history up until the 1970s is characterised by ad hoc and short term planning decisions that created an atmosphere of ‘order among chaos’. The increasing pressure of population and traffic needs as the twentieth-century progressed meant that the Junction became grimmer and more dishevelled.

The late 1960s to the early 1970s saw a harsh ‘engineering’ formality imposed over the Junction. Order through rigid form and function, which reduced congestion significantly but it also created a significant physical barrier dissecting the local community. In the Twentyfirst-century the Junction’s solution seems tired and outmoded, it is hoped that in the future any change to the Junction will involve a better balance of the needs of the commuter and the needs of the local community as well as create a space that can be used by all, which promotes their welfare, safety, health and convenience.

Footnotes

- L. Porter, 'Demographic Change', Australian Property Journal, February, 1999, pp. 389-396 at 390.

- G. Giannini, 'The Rise and Rise of Higher Density Living', Housing Futures, May/June, 2011, pp. 39-42 at 39.

- Community Alliance of Port Phillip, An overview of CAPP and our involvement in the City of Port Phillip, ca 2012, p. 2.

- St Kilda Junction Area Action Group, About us, n.d., at http://jaagstkilda.com/about/ (accessed January 6, 2014).

- L. Porter, 'Demographic Change', Australian Property Journal, February, 1999, pp. 389-396 at 391-394.

- R. Atkinson, M. Wulff, M. Reynolds and A. Spinney, Gentrification and displacement: the household impacts of neighbourhood change, AHURI Final Report No. 160, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Melbourne, 2011, p. 67.

- R. Laboto, 'Gentrification, Culture Policy and Live Music in Melbourne', Media International Australia incorporating Culture and Policy', no. 160, August, 2006, pp. 63-75 at 65.

- R. Atkinson, M. Wulff, M. Reynolds and A. Spinney, Gentrification and displacement: the household impacts of neighbourhood change, AHURI Final Report No. 160, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Melbourne, 2011, p. 47.

- S. Johanson, 'St Kilda's 'futuristic' Lego-land goes ahead', The Age, 22 August 2012; M. Baljak, 'Queueing up at the Junction', Urban Melbourne info, Thursday April 4, 2013.

- City of Port Phillip, Graffiti Management Plan 2013-2018 (Draft), 2013, p. 6.

- M. Johnston, 'Students model iconic image for a reborn St Kilda Junction', UniNews, vol. 15, no. 5, April 3-17, 2006.

- M. Perkins, 'The bad, the ugly and the dysfunctional', The Age, June 15, 2011.

- G. Coslovish, 'Welcome to Melbourne, the world's designer city, The Sydney Morning Herald, January 22, 2006, p. 7.